The Fogg Behavior Model for Persuasive Design

The BJ Fogg Behavior Model (and the B=MAT formula) offers a methodical approach to building behavior change into products, services, and marketing. A primer.

Have you ever wondered why software apps are so addictive?

Because that's how they were designed.

Technology is made to hack your attention, draw your engagement, and change your behavior.

This isn't conspiracy. It's recent history.

Technology, software, apps, and digital experiences of all kinds are persuasive by design, built to nudge people to act, to even build habits.

You should know how this works. That way as you use technology, you'll spot when tech is nudging you to change your behavior. If you work on products or services, you'll have a frame to consider how design influences your user's behavior, for better or worse. And if you're in marketing, well, persuasion should be designed into all of your messaging, your stories, and your brand.

Today's model for "persuasive design" is as easy as B=MAT, but there's much to cover, so let's dig in.

The Fogg Behavior Model

In 2009 Dr. BJ Fogg published A Behavior Model for Persuasive Design (PDF), introducing the Fogg Behavior Model ("FBM") to the world. Fogg is director of the Behavior Design Lab at Stanford University (formerly the Persuasive Technology Lab).

Here's how Fogg describes his behavior model:

The FBM asserts that for a person to perform a target behavior, he or she must (1) be sufficiently motivated, (2) have the ability to perform the behavior, and (3) be triggered to perform the behavior. These three factors must occur at the same moment, else the behavior will not happen. The FBM is useful in analysis and design of persuasive technologies. The FBM also helps teams work together efficiently because this model gives people a shared way of thinking about behavior change.

Launched in the heart of Silicon Valley, Fogg's ideas put to work immediately; for example, students of Fogg's include the cofounders of Instagram.

By 2014 the FBM was further popularized and even extended with the release of the book Hooked¹ by Fogg's protégé Nir Eyal. (See the Hook Model.²)

Behavior = M.A.T.

Fogg's model states that people will not engage in a behavior (B) unless three psychological elements are present:

M • Motivation — the person must desire to act

A • Ability — the person must have the capacity to perform the action

T • Trigger — the person must be prompted, setting in motion action

B = MAT means that ...

... A behavior won't happen without motivation.

... A behavior won't happen if a person has motivation but no ability to act.

... A behavior (still) won't happen if a person has motivation and ability, yet isn't triggered to act.

Behavior happens when all three conditions happen together. You want to design your products, services, and marketing to generate this mindset:

"I want to do it. I can do it, and now is the time to get it done."

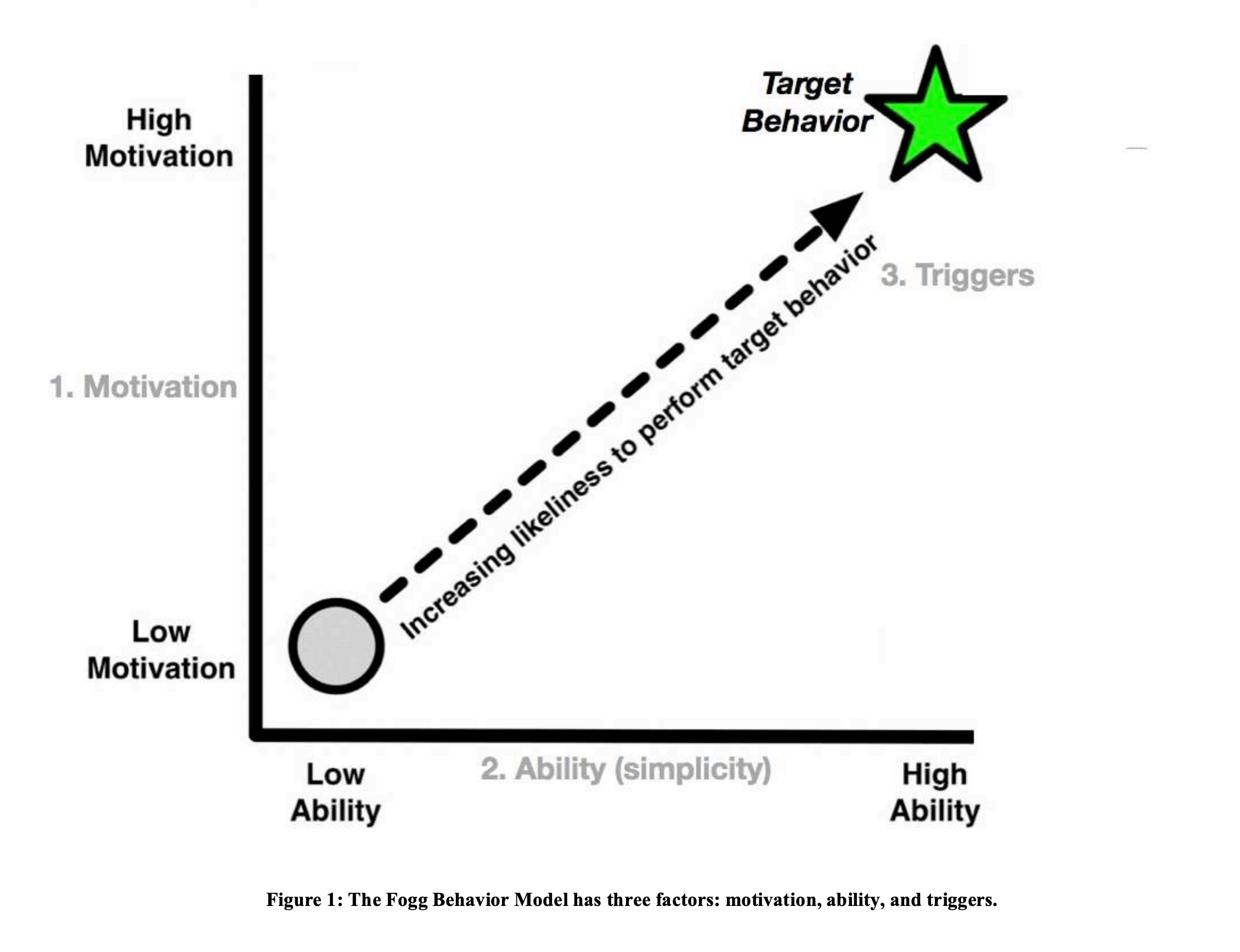

Visualizing the Fogg Behavioral Model

Fogg offers the following figure to visualize B=MAT. Motivation is on the y-axis. Ability is on the x-axis. The green star is the target behavior, realized through having matched motivation and ability and triggering the behavior:

Graphing Motivation against Ability suggests how the two can tradeoff with each other. Consider these three scenarios:

I. High motivation ✅, high ability ✅ ... behavior likely with Trigger 💥

With high ability and high motivation, all it takes is the right situation (a Trigger discussed later), for an individual to act.

II. High motivation ✅, low ability 🟡 ... what it would take to act?

With low ability and high motivation, you might assume that with or without the Trigger, nothing is going to happen. But if motivation is high enough, the person might do the work to overcome their inability — e.g. by learning a new skill or expending resources to solve for the inability (or something else entirely). For a $100,000 reward, someone with low ability may have the motivation to act.

III. Low motivation 🟡, high ability ✅ ... what would it take to act?

Similarly, the last example, when motivation is low and ability is high, you could still get a behavior under the right circumstances. A kid may not want to clean their room, but with a boost in motivation — hypothetically speaking, a parent threatening the loss of their iPad — they'll still probably do it.

Online example: persuading newsletter sign ups

In his 2009 paper, Fogg walks through persuading website visitors (like you) to sign up for an email newsletter.

Imagine you run a website. You want to get site visitors to sign up for your newsletter. Success is a visitor submitting their email address to a form. "That behavior — typing in an email address — is the target behavior."

This is easy to do. Everyone has high ability. ✅

Motivation is another story. People get too many emails and are uncertain what will happen to their information. They don't know how the newsletter will improve their life. For these visitors, low motivation 🟡 and high ability ✅ still add up to an unlikely outcome. To get that sign up for these folks, motivation must be improved (assuming signing up can't be made any easier).

On the other hand, visitors who see the existing content won't want to miss out on future installments, imagining what they might learn and believing the newsletter is for people like them. (And they can always unsubscribe.) With high ability ✅ and high motivation ✅, all they need is the trigger to act. 💥

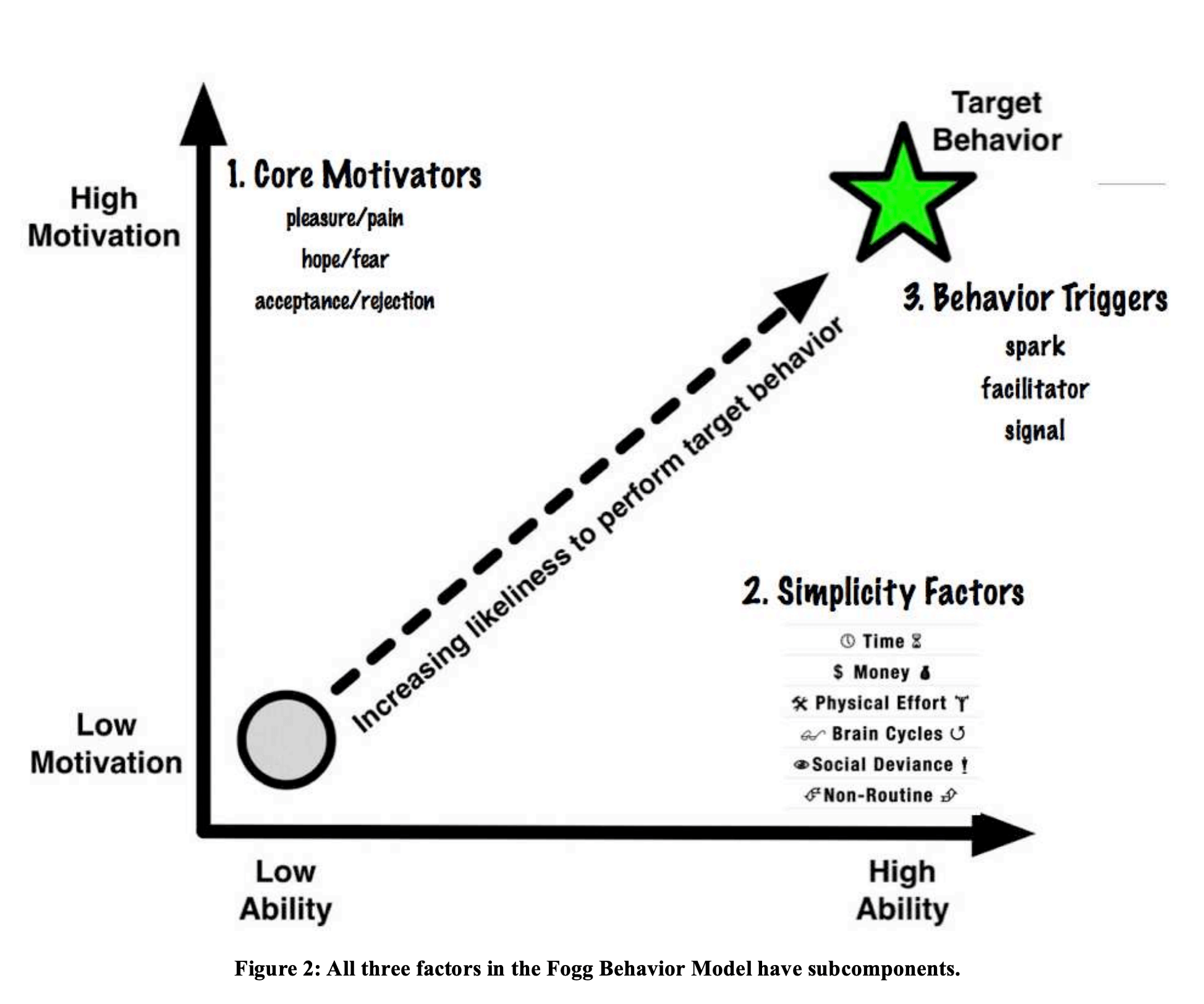

Motivation, ability, and triggers

Motivation

Fogg suggests there are three Core Motivators:

All three Core Motivators bear the dichotomy of "good versus bad," and for each motivator, you could argue the negative instance is the more potent, unethical way to persuade behavior change.

Pleasure versus pain

Fogg leads with the opposing motivators of pleasure and pain. Described by their primitive nature, pleasure and pain "function adaptively in hunger, sex, and other activities related to self-preservation and propagation of our genes."

As motivation goes, the pleasure versus pain, "carrot or the stick," set is classic. Though using pleasure and pain to motivate is risky and (potentially) unethical.

Hope versus fear

More intangible than pain and pleasure, Fogg sees the hope and fear dimensions of motivation as relating to the anticipation of future outcomes. He defines hope and fear: "Hope is the anticipation of something good happening. Fear is the anticipation of something bad, often the anticipation of loss."

The motivational power of hope — and fear — rests in their intangibility. Everyone has had fear they struggle to reason away. Hope has a way of fueling people to persevere, despite low odds of success. Both hope and fear persist. They are insatiable.

Fogg asserts that "hope is probably the most ethical and empowering motivator in the FBM." Though he doesn't say this, you might assume that fear is the least ethical motivator. The devil's in the details.

Social acceptance versus social rejection

Human beings are social animals. People need people to survive. So it's not a surprise that Fogg, like so many in his field, cites social acceptance and social rejection as Core Motivators.

Social acceptance as the positive motivator is about improving relationships and status among social connections — family, community, tribe, team. Social rejection is the need to avoid behaviors that lead to being cast out, shunned, shamed, ostracized, or otherwise marked as a negative force on the group.

Bookmark David Rock's SCARF model, which was built to aid in diagnosing motivation with social experiences through examining their impact on Status, Certainty, Autonomy, Relatedness, and Fairness.

Ability

Ability is easy to understand. How easy is it for someone to do something? But as Fogg points out, you can't overcome a lack of ability by simply training people in what they lack. Instead, Fogg sees ability as dependent upon Simplicity.

From his 2009 paper:

In real-world design, increasing ability is not about teaching people to do new things or training them for improvement. People are generally resistant to teaching and training because it requires effort. This clashes with the natural wiring of human adults: We are fundamentally lazy. As a result, products that require people to learn new things routinely fail. Instead, to increase a user’s ability, designers of persuasive experiences must make the behavior easier to do. In other words, persuasive design relies heavily on the power of simplicity. A common example is the 1-click shopping at Amazon. Because it’s easy to buy things, people buy more. Simplicity changes behaviors.

Fogg names six elements of Simplicity:

Many of the six elements are self-explanatory, and all six have to do with some form of effort, which is why some of the elements are near-equivalents (e.g. time is money).

Time

"I don't have time for this." If you don't have time to perform an action, you don't have the ability. Time problems become obvious when asking for significant time commitments. They are less obvious when the commitment required is unknown.³ How often will someone avoid doing something simply because they are uncertain about how long it will take to act? Or because it commits them to a time commitment that could go on indefinitely?

Money

Is this free, cheap, or expensive? Any behavior that requires money will have a negative effect on ability though the impact of money can vary dramatically from person to person. A wealthy person may see money as their enabler. Someone living paycheck to paycheck may bristle at the thought of another expense.

Physical Effort

If they'll have to break a sweat, they probably won't bother. No need to belabor this one: If a desired behavior requires physical effort — and let's face it, that could mean just about anything — it impacts ability.

(Also, just as time is money, Physical Effort over time can also mean money. See how these blend together?)

Brain Cycles

Don't make them think. That's the takeaway with Fogg's brain cycles. The more "mental gymnastics" required in order to act, the less likely they will take action. So be clear. Tell'em what they need to know. Tell'em what to do!

Social Deviance

Don't stand out from the crowd. Think of social deviance as breaking social norms. You ask a lot when you ask someone to act contrary to traditions and expectations of peers. (Social Deviance hurts ability and motivation.⁴)

Non-routine

Whatever someone does regularly is easy for them. Asking people to do something they lack experience with — or simply haven't done in awhile — is a break from routine, adding friction to the experience and reducing their ability to act.

The scarcest resource matters most

Fogg sees each of the six elements as "links in a chain," arguing that, "Simplicity is a function of a person’s scarcest resource at the moment a behavior is triggered." As you consider ability, try to figure out what blocks their ability most.

Solve for the constraints, then work your way through the chain.

Trigger

Prompts, cues, prods, nudges, calls to action, calls to think, or calls to feel trigger people to act.

Fogg offers three types of triggers: Sparks, Facilitators, and Signals. You can think of a triggers as the "push" people need. Sometimes that push is a notification (a Signal). Sometimes the push is the sudden addition of motivation (a Spark). Sometimes the push is the removal of an obstacle (a Facilitator).

Sparks

Sparks add motivation. Think of the flash sale on a product you already want to buy and have the money to purchase. The flash sale offers time-sensitive Core Motivator of Pleasure (that of a good deal) as Fear — avoidance of missing out on a good price. It also sweetens the pot of ability by making Money (an element of Simplicity) less of an issue. Intuitively, you know sales work. Fogg's model enumerates a few reasons why.

Facilitators

Facilitators increase ability. Consider a software product onboarding flow. These onboarding experiences may have you fill out profile information, connect your account with your contacts or other integrations, or offer tooltip walkthroughs of the product. These experiences can tax on ability and reduce the likelihood of a user trying the product.

Product onboarding flows allow you to "Skip" these steps, getting users into the product faster. The tradeoff is between time in the product — i.e. demonstrating value — rather than investment in the product.

Signals

Signals step on the gas. Signals trigger new behavior when you have both high ability and high motivation. The person is ready and able, needing only to be prompted at the right moment. Fogg writes, "An ordinary example of a signal is a traffic light that turns red or green. The traffic light is not trying to motivate me.; it simply indicates when a behavior is appropriate."

With triggers, timing is everything

Fogg makes special mention of timing and triggers in his paper, citing the ancient Greek word for "kairos — the opportune time to persuade."

When it comes to triggers, timing is everything. A notification you receive in the middle of the night — i.e. to buy that limited edition, just-released product you saved up to purchase for months — isn't going to trigger action because you're asleep.

Too often triggers are distractions: ill-timed and annoying. They can even result in decreasing motivation.

When there's a failure to act

Now that we've covered the three Core Motivators, the six elements of Simplicity (Ability), and the three types of Triggers — it's time to go back to the start and state the obvious:

The Fogg Behavior Model requires knowing the behavior you want to target. There's no use in the model if you don't know what you want someone to do. Get specific.

If you want to build a habit, break down a chain of behavior into component parts. Apply the FBM to each step, building a series of actions where one thing leads to the other, effectively causing a chain reaction of triggers.

B=MAT is simple in theory, and more complicated in practice. There will be lots of missteps in this process (and everyone is different). Whenever a behavior fails to occur, figure out which one of the three elements (MAT) is lacking and how you could adjust. Troubleshoot hiccups by asking:

- What's throttling their motivation? Pain? Fear? Social rejection?

- Do they have the ability? How could we make this simpler?

- Is there a trigger to set the behavior in motion? What extra motivation do they need? Is there a way to temporarily make it easier to act? Are they being told clearly when to act?

Don't be limited in your set of solutions. As Fogg said, "Increasing motivation is not always the solution. Often increasing ability (making the behavior simpler) is the path for increasing behavior performance."

Architects of persuasion

As mentioned at the outset of this article, behavior change is built directly into software, apps, services, and digital experiences every day.

Understanding the Fogg Behavior Model will help you spot when you're being nudged by technology.

Do what you will with that awareness.

The FBM may also help you rethink how your product or service is designed, offering your team levers to pull to increase motivation or ability or frequency of behavior.

Like other frames on R-ght, the FBM is a tool whereby you can build — or refine — your messaging, stories, and brand to be more persuasive by design.

This article is part of a growing collection of frames for understanding what's right for people — in order to build better businesses, products, and services.

Get further installments by subscribing to R-ght.

Footnotes

¹ If you search for "required reading for building addictive apps" you get a Google knowledge card pointing you to Hooked, and Hooked on Amazon is the no. 1 search result (receipt).

² The Hook Model is a loop: Trigger → Action → Reward → Investment, which then leads to a repeat of the loop. Eyal's Hook Model has had untold influence on app design. Apps motivate through built in Rewards (and these rewards are often randomly given, applying concepts historically used in the design of casino slot machines) and Investment (e.g. all the content you create on a social media platform further binds you to that platform). If you build products, knowing the Hook Model is a must, and Eyal's book is an easy read.

³ In this case, while Time impacts Ability, it also hurts motivation by introducing fear of the unknown. This is a good example of how there's a muddiness to these concepts, where one Core Motivator or element of Simplicity can bleed into another.

⁴ Yes, Social Deviance as an element of Simplicity directly connects to the fear of social rejection, two of Fogg's Core Motivators. Though this feels "messy" to have social elements in Ability and Motivation, I'd interpret this redundancy as an example of just how powerful social aspects are for behavior change. It's also why Rock's SCARF model is so useful outside of understanding what motivates social experiences.