The Jobs-to-Be-Done framework

What do milkshakes teach us about people? This primer on the Jobs to Be Done "JTBD" framework provides a way to figure out the hidden, unmet desire behind why someone buys a product, as pioneered by Clayton Christensen.

People don’t want to buy a quarter-inch drill. They want a quarter-inch hole!

— Theodore Levitt

Clayton Christensen makes a simple case: If you want to understand what motivates people to act, first understand what it is they hope to get done.

Understand the why behind the what.

Christensen — the late author of The Innovator’s Dilemma — first articulated this concept in a 2005 paper titled The Cause and the Cure of Marketing Malpractice (hbr.org). He wrote:

When people find themselves needing to get a job done, they essentially hire products to do that job for them. The marketer’s task is therefore to understand what jobs periodically arise in customers’ lives for which they might hire products the company could make. If a marketer can understand the job, design a product and associated experiences in purchase and use to do that job, and deliver it in a way that reinforces its intended use, then when customers find themselves needing to get that job done, they will hire that product.

Christensen’s theory, while aimed at marketers in the above article, has become a bedrock concept in product development over the last twenty years. Known now as the “Jobs” or “Jobs to Be Done” theory (“JTBD”), the approach is summed up with a simple, provocative question:

What is the job a person hires a product to do? What is the job to be done?

The Job to Be Done: Satisfy hunger on your daily commute

To illustrate his Job to Be Done concept, Christensen told a simple story about a fast food company wanting to make a better milkshake.

The fast food company, which might as well be McDonald's, took a classic approach:

- The identified their target milkshake-slurping demographic.

- They researched their audience, investigating milkshake preferences.

- They implemented their findings through a revised milkshake product offering.

- They found the new milkshakes didn’t improve milkshake sales whatsoever.

What went wrong and what did they learn in the process? Take the four minutes to listen to the delightful story from Christensen below:

Christensen tells the milkshake story so well that we recommend you give him a listen in the YouTube video above. Alternatively, the story is transcribed below.

🥤 Transcript of Clayton Christensen's Milkshake Story

Clay Christensen: We actually hire products to do things for us. And understanding what job we have to do in our lives for which we would hire a product is really the key to cracking this problem of motivating customers to buy what we’re offering.

So I wanted just to tell you a story about a project we did for one of the big fast food restaurants. They were trying to goose up the sales of their milkshakes. They had just studied this problem up the gazoo. They brought in customers who fit the profile of the quintessential milkshake consumer. They’d give them samples and ask, “Could you tell us how we could improve our milkshakes so you’d buy more of them? Do you want it chocolate-ier, cheaper, chunkier, or chewier?”

They’d get very clear feedback and they’d improve the milkshake on those dimensions and it had no impact on sales or profits whatsoever.

So one of our colleagues went in with a different question on his mind. And that was, “I wonder what job arises in people’s lives that cause them to come to this restaurant to hire a milkshake?” We stood in a restaurant for 18 hours one day and just took very careful data. What time did they buy these milkshakes? What were they wearing? Were they alone? Did they buy other food with it? Did they eat it in the restaurant or drive off with it?

It turned out that nearly half of the milkshakes were sold before 8 o’clock in the morning. The people who bought them were always alone. It was the only thing they bought and they all got in the car and drove off with it.

To figure out what job they were trying to hire it to do, we came back the next day and stood outside the restaurant so we could confront these folks as they left milkshake-in-hand. And in language that they could understand we essentially asked, “Excuse me please but I gotta sort this puzzle out. What job were you trying to do for yourself that caused you to come here and hire that milkshake?”

They’d struggle to answer so we then helped them by asking other questions like, “Well, think about the last time you were in the same situation needing to get the same job done but you didn’t come here to hire a milkshake. What did you hire?”

And then as we put all their answers together it became clear that they all had the same job to be done in the morning. That is that they had a long and boring drive to work and they just needed something to do while they drove to keep the commute interesting. One hand had to be on the wheel but someone had given them another hand and there wasn’t anything in it. And they just needed something to do when they drove. They weren’t hungry yet but they knew they would be hungry by 10 o’clock so they also wanted something that would just plunk down there and stay for their morning.

[Christensen, paraphrasing the milkshake buyer:] “Good question. What do I hire when I do this job? You know, I’ve never framed the question that way before, but last Friday I hired a banana to do the job. Take my word for it. Never hire bananas. They’re gone in three minutes — you’re hungry by 7:30am.

“If you promise not to tell my wife I probably hire donuts twice a week, but they don’t do it well either. They’re gone fast. They crumb all over my clothes. They get my fingers gooey.

“Sometimes I hire bagels but as you know they’re so dry and tasteless. Then I have to steer the car with my knees while I’m putting jam on it and if the phone rings we got a crisis.

“I remember I hired a Snickers bar once but I felt so guilty I’ve never hired Snickers again.

“Let me tell you when I hire this milkshake it is so viscous that it easily takes me 20 minutes to suck it up through that thin little straw. Who cares what the ingredients are — I don’t.

“All I know is I’m full all morning and it fits right here in my cupholder.”

Christensen: Well it turns out that the milkshake does the job better than any of the competitors, which in the customer’s minds are not Burger King milkshakes but bananas, donuts, bagels, Snickers bars, coffee, and so on.

I hope you can see how if you understand the job, how to improve the product becomes just obvious.

Confusing the consumer with the consumption

Christensen’s story about milkshakes illustrates how direct questions can steer you in the wrong direction. In this case, asking the milkshake buyer, “What would make our milkshakes better?” was a fast way to go the wrong direction.

In this case, morning milkshake buyers are assumed, incorrectly, to be buying the tasty treats because they want a specific type of dessert.

Only by observing the customer's behavior and probing indirectly can you figure out their hidden, unstated desires.

Method to the madness

Christensen's Jobs to Be Done framework brings to our attention something everyone knows. We all have reasons for the choices they make! Shakespeare wrote about this fundamental facet of people 400 years ago in Hamlet, scripting, “Though this be madness yet there is method in it.”

When it comes to people, action always has a purpose, even if that purpose is hidden from the actor. Consider a few examples below:

- The parent drives a "suped up" SUV made for offroading only to never take it off the street. Why? Because they want to feel rugged, strong, and outdoorsy.

- The businessperson wears a suit not only to impress others but to feel impressive and confident too.

- The teen rebels against their parents advice not because its wrong but because they want to feel independent.

Seeking out the Job to Be Done, the "method to the madness," is about having empathy for the user. It's about asking, "How is this right for them?" You must doggedly seek out that knowledge, looking for what they hope to achieve.

When it comes to building products, success is in the application of what you learn about the desires of people. That’s why it’s important to question whether the new, impressive product or service feature does, in fact, help the customer fulfill their needs.

If the development advanced is done without the customer need in focus, we might find we’ve developed the most amazing product that no one wants.

Apply the Jobs to Be Done frame to develop remarkable products

Applying the JTBD framework can be as simple as asking, “What did you turn to the last time you needed to do this?”

In Clay Christensen’s milkshake story, that question helped consumers to think back on a previous time they were in the same situation and needed that specific job done. The milkshake buyer needed to satiate their hunger — and their boredom — on their long commute to work.

Teasing out just what it is the customer wants done benefits from careful observation and a heaping dose of abductive reasoning. Below are three approaches to try when you're trying to apply the Jobs to Be Done framework.

1. The switching question

Is your product so good that your audience would ‘fire’ their current product in order to hire yours?

What product did your customer “fire” before hiring their current product? What did the old product do well? What didn't it do well enough? What's in common between the old and new products?

You can apply the “fired” lens of the Jobs to Be Done framework to understand how many once-successful businesses were displaced by competitors that simply did the job better.

Here are a few examples:

- Netflix, replacing Blockbuster — “I need something to entertain me”

- Uber, Lyft, replacing taxis — “I need to get from point A to point B”

- Google, replacing libraries and directories, “I need [some information]”

- Amazon, replacing retail stores, “I need [some product]"

- Smartphones, replacing [everything] — “I need [everything]”

If the product is only an idea, here's the question to ask: “Will this product or service be so good that my intended customer will take a chance on mine?"

If your product or service isn't "10X better" than the incumbent product, your intended customer may say, "No, thanks." They might also pass on your your product because of the perceived uncertainty and risk of a new product. (See how uncertainty plays into the development of desire paths.)

This question is at the center of a 2013 post from Jason Fried, channeling JTBD he wrote, “What are people going to stop doing once they start using your product?”

When you’re building a new product, you’re often thinking about all the new things people are going to be able to do with it. Now they can do this, now they can do that. Exciting!

But there’s a better question to ask: What are people going to stop doing once they start using your product?

What does your product replace? What are they switching from? How did they do the job before your product came along?

Habit, momentum, familiarity, anxiety of the unknown – these are incredibly hard bonds to break. When you try to sell someone something, you have to overcome those bonds. You have to break the grip of that gravity.

So, when you’re thinking about your product, think about what it replaces, not just what it offers. What are you asking people to leave behind when they move forward with you? How hard will that be for them? How can you help them overcome everything that’s tugging them in the opposite direction?

Be honest. If you can’t answer the “switching jobs” question clearly, could you reasonably expect a potential customer to?

2. The W.W.Y.S.Y.D.H.? question

What does your product or service actually do for the customer?

If you’ve seen office space, you certainly remember when “the Bobs” asked our slacker protagonist a simple question: “What would you say you do here?”

Answer this simple, straight-to-the-point question enough and you might just tease apart what job it is your customer is trying to get done.

Be specific, general, and comprehensive. The details may be relevant in surprising ways:

🪛 Drills: The drill avoids hand fatigue. The drill offers power. The drill offers speed. The drill makes holes.

🥤 Milkshakes: The milkshake is a treat. The milkshake is cold. The milkshake can be consumed through a straw. The milkshake takes awhile to drink.

☕️ Starbucks: Starbucks makes good coffee. Starbucks gives you energy. Starbucks makes you feel classy, professional. Starbucks offers you a place to go. Etc.

Make a W.W.Y.S.Y.D.H. list. Contrast your list with the product’s stated features. Do the features you developed solve for the things on your list — the things your customers need doing? How?

Consider this analogy to an actual job:

- W.W.Y.S.Y.D.H. is the day-to-day, on-the-job stuff you do.

- Your job description is like the product feature list.

When you do JTBD right, how they use the product is reflected in how you market and talk about the product. The two should be congruent and complement each other.

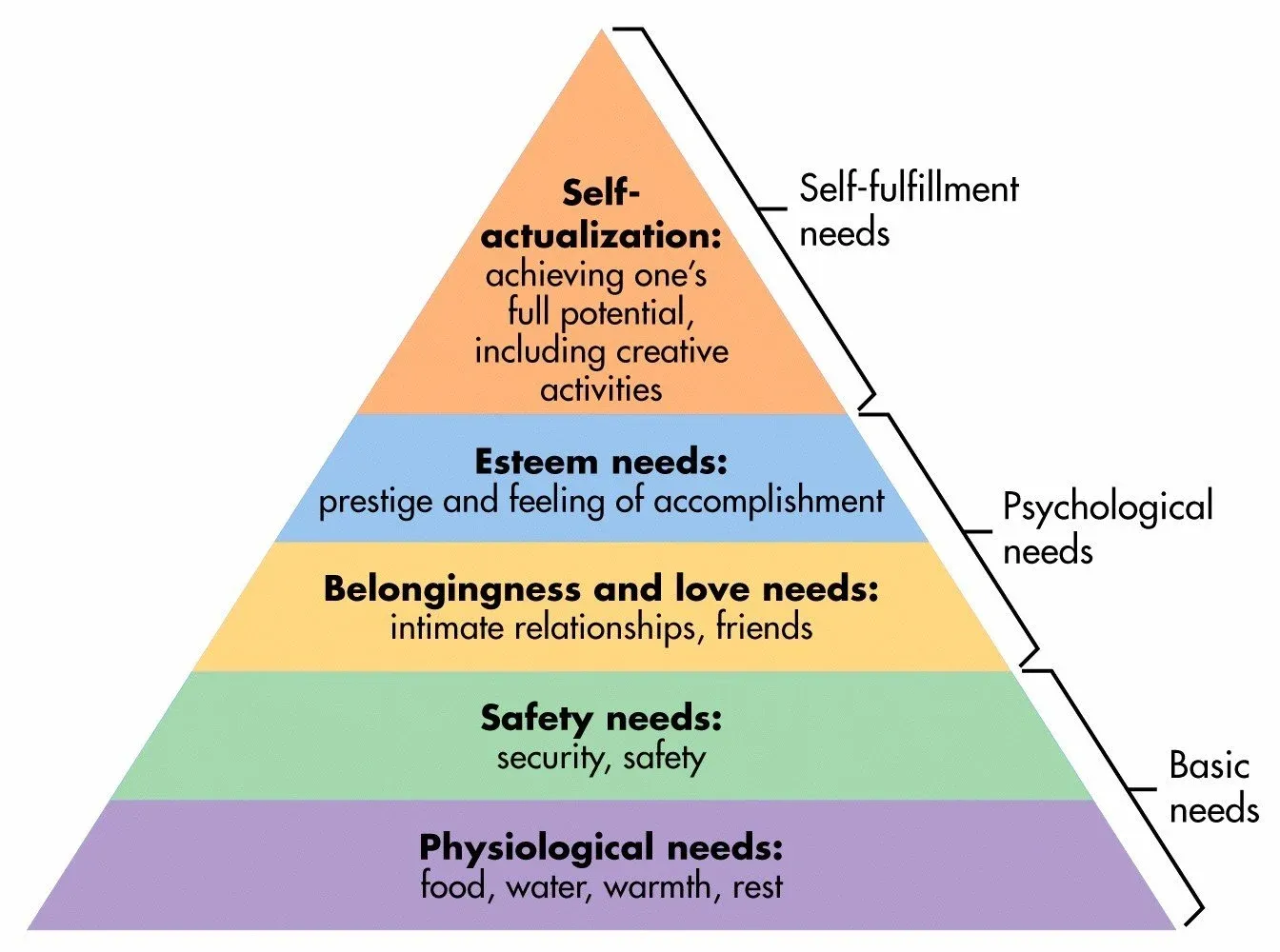

3. The hierarchy of needs question

How does the product meet a customer's hierarchy of needs?

In contemplating what your product or service actually does — W.W.Y.S.Y.D.H. — go high-level and think about Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Christensen has written that, “With few exceptions, every job people need or want to do has a social, a functional, and an emotional dimension.”

- What social need does the product or service solve?

- What emotional need is being solved by the product or service?

- How will using the product or service make the customer feel?

It can be difficult to imagine how a given product or service solves a customer's intangible needs, but it makes perfect sense. You can even practice asking these questions of yourself! What is the Job to Be Done of a hobby, a relationship, anything.

Apply the Jobs to be Done framework introspectively to your own wants and needs and you might discover something new about yourself.

Use Jobs to Be Done and build better products and services

As you work to improve your existing products and services — or seek to extend your offerings — don't forget the Job to Be Done.

Apply the JTBD frame to every business decision and you'll always have customers ready to hire your product for that job.

This is part of a growing collection of frames for understanding what's right for people — in order to build better businesses, products, and services.

Additional resources on Jobs to Be Done

- JTBD has also made its way into a new book (2016) called Competing Against Luck by Clayton Christensen.

- Bob Moesta, President of the Re-Wired Group, is another prominent voice behind the jobs-to-be-done theory. Check out this podcast he gave on JTBD.

- Also see The Innovator’s Dilemma for insights into disruptive innovation.