Mouthguard

The loudest, clearest message you can send won't take words.

A friend of mine Jamesⁱ trains Muay Thai — a.k.a. Thai boxing or the "Art of eight limbs" — a martial art used by MMA fighters.

One day James finished up training, changed clothes, and went directly from the gym to a bar to catch up with a buddy.

Sitting at the high-top, James was approached by a tipsy stranger. This fella was in a foul mood and got to goading James, provoking him, wanting to start a fight.

James told the man he wasn't interested and brushed off the advances.

The jerk persisted.

James grew tired of dealing with the belligerent, "You want to fight? Fine." He stood up, reached in his back pocket, and pulled out his mouthguard, which he still had from training.

Soon as James placed the guard into his mouth, the stranger jolted back, putting distance between them. His arms shot outward, placating.

"Whoa okay, okay! Take it easy ... I didn't mean anything by it!"

The would-be assailant walked off, tail between his legs. The fight was over before it even began.

All because of a mouthguard.

Show. Don't tell.

At the bar, the antagonist had no idea James trained in Muay Thai, and James had no idea pulling his mouthguard out would send such a powerful message.

Had James told the guy he trained Muay Thai, would it have mattered? Maybe. Probably not. In fact, had James tried to explain his combat know-how, it's likely to have had the opposite effect.

Prove it, tough guy.

Actions are raw, hard-to-fake communication. That's what makes them so powerful. Everyone knows that talk is cheap, that money talks and bullshit walks. That's why you show (don't tell), and why actions speak louder than words.

Action is the most potent form of communication because doing something almost always costs more than saying something. Actions have consequences, both the desired outcomes of acting and the unintended consequences too.

Those unintended consequences serve as signals.

Consider the mouthguard. Used to protect against injury, a mouthguard isn't expensive. A mouthguard won't make you a better fighter. So why would anyone carry one around? Why would anyone so casually pull it out and put it on before getting into a bar fight?

Because that person knows how to fight. Because they know how to take a blow to the face. Because they know how to hit back. Not because they carry a mouthguard around in case of emergency bar fights — because that would make them crazy. (Though that'd just be another reason to back away from a fight.)

James' action signaled more than he could ever say because of what it implied.

Unseen signals

Apple launched the Macintosh computer back in 1984. The Apple Macintosh was a computer made for anyone and everyone, a personal computer.

To Steve Jobs, the Macintosh was also art.

According to Andy Hertzfeld, one of the Mac's first software engineers, the Macintosh team aspired to more than money. Hertzfeld wrote they "... had a complicated set of motivations, but the most unique ingredient was a strong dose of artistic values. First and foremost, Steve Jobs thought of himself as an artist, and he encouraged the design team to think of ourselves that way, too. The goal was never to beat the competition, or to make a lot of money; it was to do the greatest thing possible, or even a little greater."

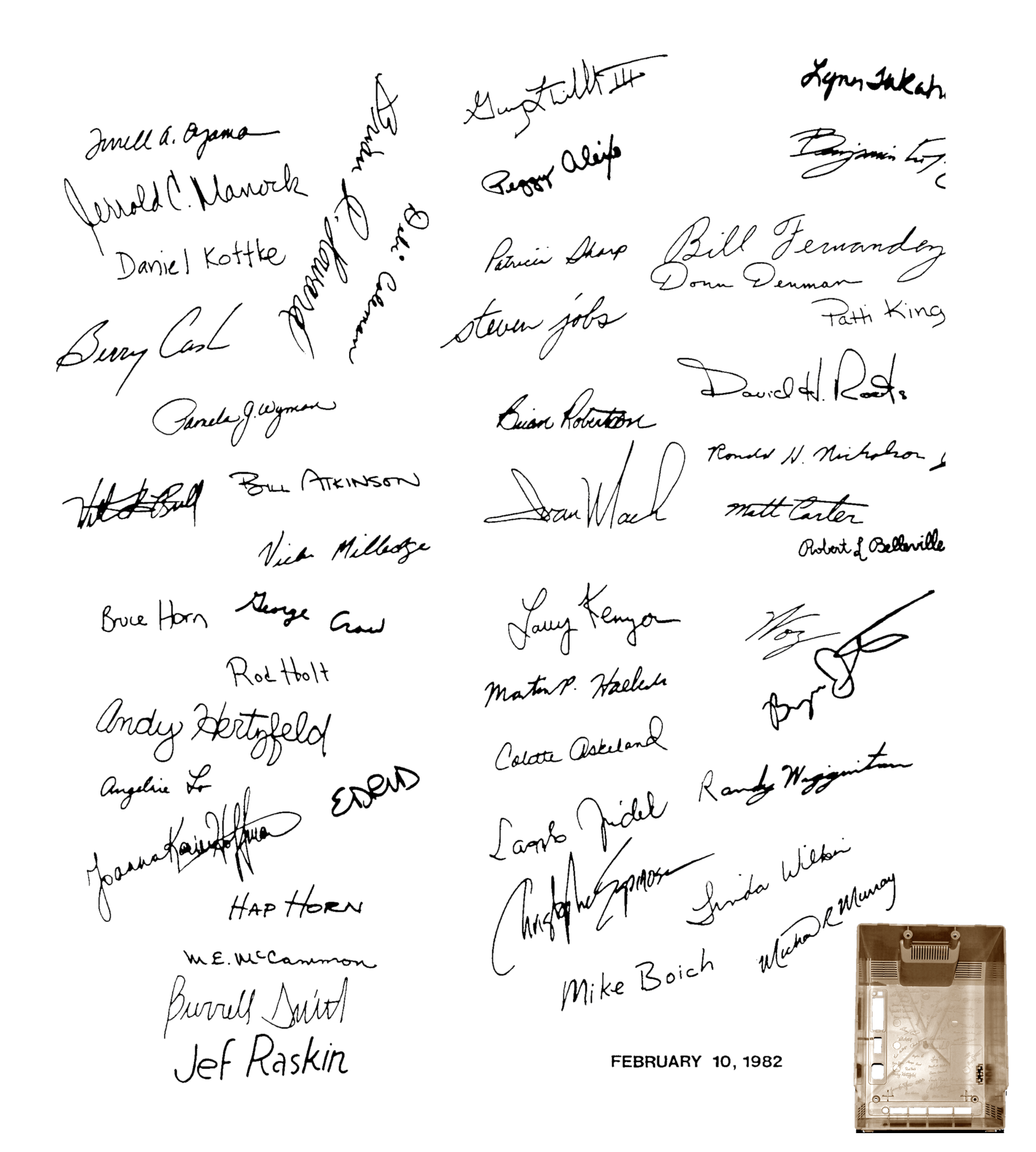

In 1982, the design of the hard plastic case of the Macintosh neared completion. The computer was almost ready for mass production. Jobs brought the team together for a special event.

As Hertzfeld recalls, "Since the Macintosh team were artists, it was only appropriate that we sign our work. Steve came up with the awesome idea of having each team member's signature engraved on the hard tool that molded the plastic case, so our signatures would appear inside the case of every Mac that rolled off the production line."

But these signatures would appear inside the Macintosh computer case — a case requiring an uncommon tool to open. Most Mac buyers would never see them.

Expensive to do and adding nothing to the product, what was the point?

The best signals are byproducts

When the Apple Macintosh launched, computing changed forever.

The first Mac had many firsts. It was the first mass-market desktop computer with a built-in screen. It was the first PC with a user-friendly graphical user interface. It introduced the mouse. It even came in a bag and had a handle. The product was remarkable, made with a passion you can't fake.

The product made Apple.

Those signatures shipped with every computer, and though no Mac buyer knew it at the time, the Mac team knew. To them, their names bound them to their work, symbolizing the pride they felt in their creation. The signatures were a byproduct of their aspiration to build "the greatest thing possible, or even a little greater."

Forty years later, people collect the original Macintosh. Many collectors open up the case and remark at all those names.

What was an unseen signal now stands for the pursuit of excellence built into Apple products.

Signals you can't fake

The mouthguard didn't turn James into a deadly brawler. The case signatures didn't make the Mac any more innovative. Yet both, though insignificant alone, suggest great significance.

Signals are byproducts of excellence in action.

If you want to build a product and a brand that changes perspectives, you can't fake the work. You have to do the work to be great — even when it has no benefit to the bottom line. Only then will you send a clear signal to the world.

Because the truth is always there, even if it lies beneath the surface.

This is part of a growing collection of parables and stories used to understand people — in order to build better businesses, products, and services.

Get further installments by subscribing to R-ght.

ⁱ Note that "James" is a friend of a friend and not his real name.