Pre-Suasion by Robert Cialdini

How do you influence people by indirectly preparing them to be influenced? Find out in Robert Cialdini's second book on persuasion, Pre-Suasion. A review and quotes.

Dr. Robert B. Cialdini wrote the book on influence in 1984. Literally. That book, titled Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion, detailed six Principles of Persuasion: Reciprocation, Consistency (and commitment), Social Proof, Liking, Authority, and Scarcity.¹

Influence established Cialdini as the go-to expert on persuasion, suggesting how to wield influence in marketing and business.

In 2016, three decades and several million copies sold later, Cialdini published his second book: Pre-Suasion: A Revolutionary Way to Influence and Persuade (Amazon). The focus of Pre-Suasion centers on the influence of focus — i.e. directing attention is key to persuasion. Like the magician directing the audience's attention to pull off their legerdemain (sleight of hand) to great applause, Pre-Suasion explains how directing attention through "openers" prepares a person to be persuaded.

Cialdini sums up pre-suasion:

"[Pre-Suasion] identifies what savvy communicators do before delivering a message to get it accepted."

As well as:

"... a core tenet of pre-suasion: immediate, large-scale adjustments begin frequently with practices that do little more than redirect attention."

At less than 250 pages long, Pre-Suasion is a quick, insightful read that will expand your understanding about persuasion — and how you can be influenced indirectly.

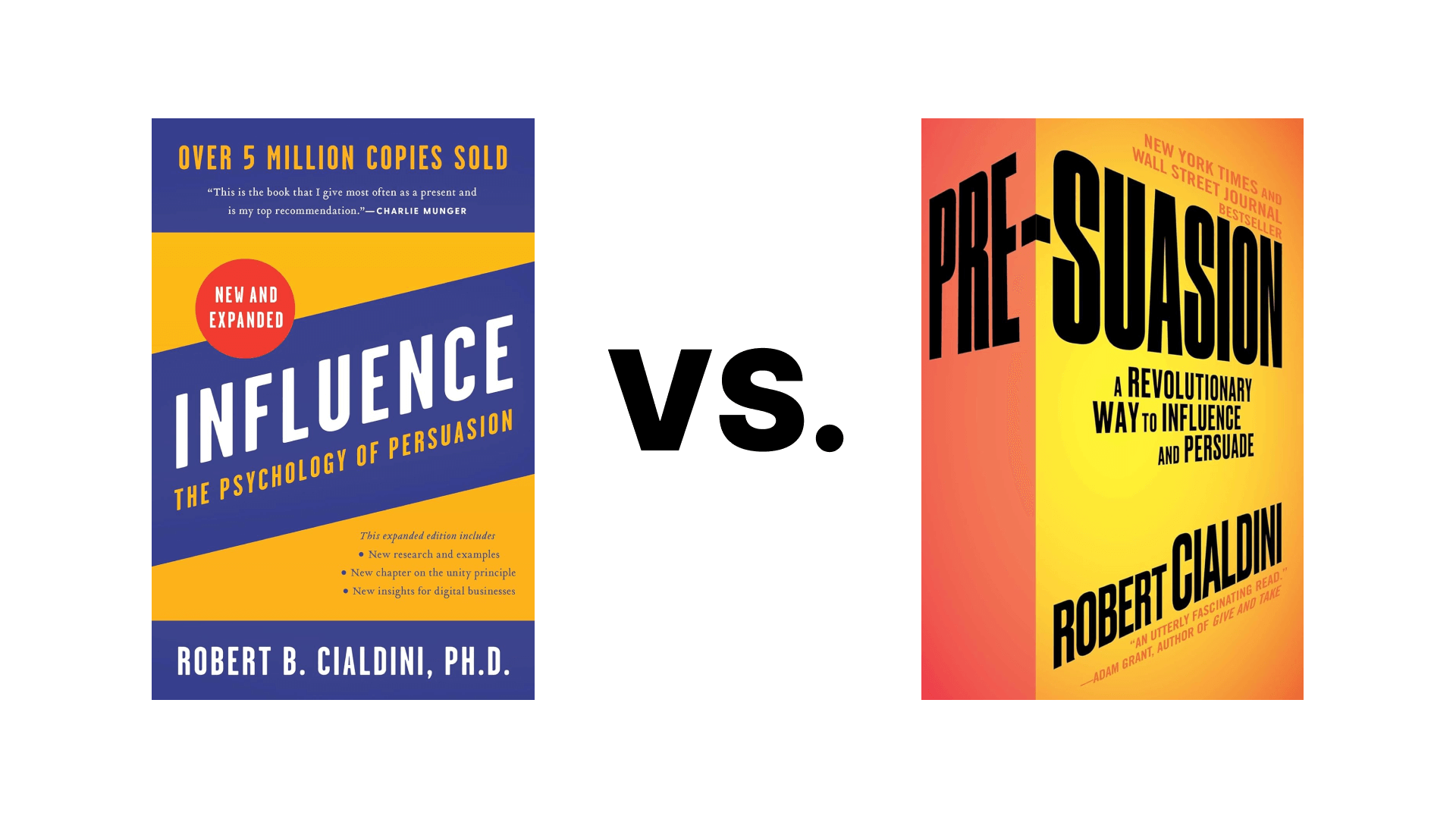

Pre-Suasion vs. Influence

You might be wondering if you can read only one of Cialdini's books. The answer is: No. Each covers different aspects of persuasion.

Influence establishes Cialdini's Principles of Persuasion: Reciprocation, Consistency (and Commitment), Social Proof, Liking, Authority, Scarcity, Unity.¹ These principles capture the "broad strokes" used to persuade people.

According to Cialdini, they are "highly effective general generators of acceptance because they typically counsel people correctly regarding when to say yes to influence attempts." In other words, people naturally respond to these principles because they have historically correlated with good outcomes.

There's much more to Influence, including the stories and research Cialdini shares to illustrate and educate the reader on these principles.

Pre-Suasion establishes how to lay the groundwork for persuasion to happen. Cialdini explains how priming people — i.e. directing their attention or focus — readies them for persuasion. You might think of this as creating conditions more favorable to persuasion. Cialdini summarizes Pre-Suasion as:

"In large measure, who we are with respect to any choice is where we are, attentionally, in the moment before the choice. We can be channeled to that moment by (choice-relevant) cues we haphazardly bump into in our daily settings; or, of greater concern, by the cues a knowing communicator has tactically placed here; or, to much better and lasting effect, by the cues we have stored in those recurring sites to send us consistently in desired direction. In each case, the made moment is pre-suasive. Whether we are wary of the underlying process [of pre-suasion], attracted to its potential, or both, we'd be right to acknowledge its considerable power and wise to understand its inner workings."

One example detailed in Pre-Suasion is Cialdini's agenda-setting theory, which is a simple way to understand the indirect influence of media.

In both books, Cialdini discusses the ethics of persuasion. Rather than become mired in debate over persuasion, as Cialdini said in the final sentence quoted above "we'd be right to acknowledge its considerable power and wise to understand its inner workings."

Awareness of pre-suasion matters because pre-suasion so often occurs outside of conscious awareness. Awareness is a powerful defense.

Pre-Suasion: A Revolutionary Way to Influence and Persuade

Cialdini’s Pre-Suasion draws on his extensive experience as the most cited social psychologist of our time and explains the techniques a person should implement to become a master persuader. Altering a listener’s attitudes, beliefs, or experiences isn’t necessary, says Cialdini—all that’s required is for a communicator to redirect the audience’s focus of attention before a relevant action.

Quotes from Pre-Suasion

Below are selected quotes from Robert Cialdini's book Pre-Suasion, each available below the toggle.

All quotes are in chronological order from the book with page numbers noted from the hardback. Emphasis added by R-ght.

How to change behavior — the dominant model

pp. 23–24

"[The dominant scientific model of social influence advises as follows: If] you wish to change another's behavior, you must first change some existing feature of that person so that it fits with the behavior. If you want to convince people to purchase something unfamiliar—let's say a new soft drink—you should act to transform their beliefs or attitudes or experiences in ways that make them want to buy the product. You might attempt to change their beliefs about the soft drink by reporting that it's the fastest-growing new beverage on the market; or to change their attitudes by connecting it to a well-liked celebrity; or to change their experiences with it by offering free samples in the supermarket. Although an abundance of evidence shows that this approach works, it is now clear that there is an alternate model of social influence that provides a different route to persuasive success."

Editorial note: That alternate model is pre-suasion.

Establishing agenda-setting theory

pp. 33–34

"... a communicator who gets an audience to focus on a key element of a message pre-loads it with importance. This form of pre-suasion accounts for what many see as the principle role (labeled agenda setting) that the news media play in influencing public opinion. The central tenant of agenda-setting theory is that the media rarely produce change directly, by presenting compelling evidence that sweeps an audience to new positions; they are much more likely to persuade indirectly, by giving selected issues and facts better coverage than other issues and facts. It's this coverage that leads audience members—by virtue of the greater attention they devote to certain topics—to decide that these are the most important to be taken into consideration when adopting a position. As the political scientist Bernard Cohen wrote, 'The press may not be successful most of the time in telling people what to think, but it is stunningly successful in telling them what to think about.' According to this view, in an election, whichever political party is seen by voters to have the superior stance on the issue highest on the media's agenda at the moment will likely win.

"That outcome shouldn't seem troubling provided the media have highlighted the issue (or set of issues) most critical to the society at the time of the vote. Regrettably, other factors often contribute to coverage choices, such as whether a matter is simple or complicated, gripping or boring, familiar or unfamiliar to newsroom staffers, inexpensive or expensive to examine, and even friendly or not to the news director's political leanings."

See the article on Agenda-setting theory

On the importance of managing background information

p. 41

"Classrooms with heavily decorated walls displaying lots of posters, maps, and artwork reduce the test scores of young children learning science material there. It is clear that background information can both guide and distract focus of attention; anyone seeking to influence optimally must manage that information thoughtfully."

"What's focal is causal"

p. 51

"Therefore, directed attention gives focal elements a specific kind of initial weight in any deliberation. It gives them standing as causes, which in turn gives them standing as answers to that most essential of human questions: Why?

"Because we typically allot special attention to the true causes around us, if we see ourselves giving such attention to some factor, we become more likely to think of it as a cause."

On wandering eyes

p. 70

"In a survey, college students in a romantic partnership were asked I a series of standard questions that normally predict the stability of relationships: questions about how much in love they were with their partner, how satisfied they were with the relationship, how long they wanted to be in the relationship, and so on. In addition, the survey included some new questions for the participants that inquired into attentional factors such as how much they noticed and were distracted by good-looking members of the opposite sex. Two months after the survey, the participants were recontacted and asked if their relationships had remained intact or had ended. Remarkably, the best indicator of a breakup was not how much love they felt for their partner two months earlier or how satisfied they were with their relationship at that time or even how long they had wanted it to last. It was how much they were regularly aware of and attentive to the hotties around them back then."

To fit in or to stand out

pp. 74—75

"We also realized that these two contrary motivations, to fit in and to stand out, map perfectly onto a pair of longtime favorite commercial appeals. One, of the 'Don't be left out' variety, urges us to join the many. The other, of the 'Be one of the few' sort, urges us to step away from the many. So, which would an advertiser be better advised to launch into the minds of prospects? Our analysis made us think that the popularity-based message would be the right one in any situation where audience members had been exposed to frightening stimuli—perhaps in the middle of watching a violent film on TV—because threat-focused people want to join the crowd. But sending that message in an ad to an audience watching a romantic film on TV would be a mistake, because amorously focused people want to step away from the crowd.

...

"Although the data pattern seems complex, it becomes simplified when viewed through the prism of a core claim of this book: the effectiveness of persuasive messages—in this case, carrying two influence themes that have been commonly used for centuries—will be drastically affected by the type of opener experienced immediately in advance. Put people in a wary state of mind via that opener, and, driven by a desire for safety, a popularity-based appeal will soar, whereas a distinctiveness-based appeal will sink. But use it to put people in an amorous state of mind, and, driven by a consequent desire to stand out, the reverse will occur."

The investigatory reflex and the doorway effect

pp. 77–78

"It finally dawned on Pavlov that he could account for both breakdowns in the same way: upon entering a new space, both he and the visitors became novel (new) stimuli that hijacked the dog's attention, diverting it from the bell and food while directing it to the changed circumstances of the lab. Although he was not the first scientist to notice this type of occurrence, Pavlov recognized its purpose in the label he gave it: the investigatory reflex. He understood that in order to survive, any animal needs to be acutely aware of immediate changes to its environment, investigating and evaluating these differences for the dangers or opportunities they might present. So forceful is this reflex that it supersedes all other operations.

"The potent effect of a rapid change in environmental circumstances on human concentration can be seen in a mundane occurrence that afflicts us all. You walk from one room to another to do something specific, but, once there, you forget why you made the trip. Before cursing your faulty powers of recollection, consider the possibility of a different (and scientifically documented) reason for the lapse: walking through doorways causes you to forget because the abrupt change in your physical surroundings redirects your attention to the new setting—and consequently from your purpose, which disrupts your memory of it. I like this finding because it offers a less personally worrisome account of my own forget. fulness. I get to say to myself, "Don't worry, Cialdini, it wasn't you; it was the damned doorway."

"You" as an opener

p. 84

"Here, then, is another lesson in pre-suasion available for your use when you have a good case to make, you can employ—as openers—simple self-relevant cues (such as the word you) to predispose your audience toward a full consideration of that strong case before they see or hear it."

The next-in-line effect

p. 84

"Even though I was sitting in the front row as the dance unfolded, I never saw it. I missed it completely, and I know why: I was focused on myself and my upcoming speech, with all of its associated phrasings and transitions and pauses and points of emphasis. The missed experience is one of my enduring regrets—it was Balanchine, Stravinsky, etc., after all. I'd been the victim of what behavior scientists call the next-in-line effect, and, as a consequence, I have since figured out how to avoid it and even use it on my behalf. You might be able to do the same."

The Zeigarnik effect

pp. 86–87

"To test this logic, Zeigarnik performed an initial set of experiments that she, Lewin, and numerous others have used as the starting point for investigating what has come to be known as the Zeigarnik effect. For me, two important conclusions emerge from the findings of now over six hundred studies on the topic. First (and altogether consistent with the beer garden series of events), on a task that we feel committed to performing, we will remember all sorts of elements of it better if we have not yet had the chance to finish, because our attention will remain drawn to it. Second, if we are engaged in such a task and are interrupted or pulled away, we'll feel a discomforting, gnawing desire to get back to it. That desire—which also pushes us to return to incomplete narratives, unresolved problems, unanswered questions, and unachieved goals—reflects a craving for cognitive closure."

The mystery technique

p. 91

"In addition, there was something about this discovery that struck me as more than a little curious—something I'll tee up, unashamedly, as a mystery: Why hadn't I noticed the use of this technique before, much less its remarkably effective functioning in popularized scholarship? After all, I was at the time an avid consumer of such material. I had been buying and reading it for years. How could the recognition of this mechanism have eluded me the whole while?

"The answer, I think, has to do with one reason [the mystery technique] is so effective: it grabs readers by the collar and pulls them in to the material. When presented properly, mysteries are so compelling that the reader can't remain an aloof outside observer of story structure and elements. In the throes of this particular literary device, one is not thinking of literary devices; one's attention is magnetized to the mystery story because of its inherent, unresolved nature."

Medical student syndrome

pp. 121–122

"In Germany, audience members listening to a lecture on dermatological conditions typically associated with itchy skin immediately felt skin irritations of their own and began scratching themselves at an increased rate.

"This last example offers the best indication of what's going on, as it seems akin to the well-known occurrence of 'medical student syndrome.' Research shows that 70 percent to 80 percent of all medical students are afflicted by this disorder, in which they experience the symptoms of whatever disease they happen to be learning about at the time and become convinced that they have contracted it. Warnings by their professors to anticipate the phenomenon don't seem to make a difference; students nonetheless perceive their symptoms as alarmingly real, even when experienced serially with each new 'disease of the week.' An explanation that has long been known to medical professionals tells physician George Lincoln Walton wrote in 1908:

"'Medical instructors are continually consulted by students who fear that they have the diseases they are studying. The knowledge that pneumonia produces pain in a certain spot leads to a concentration of attention upon that region [italics added], which causes any sensation there to give alarm. The mere knowledge of the location of the appendix transforms the most harmless sensations in that region into symptoms of serious menace."

3 behaviors to increase happiness by shifting attention

p. 125

"On the one hand, [Dr. Sonja Lyubomirsky] specified a set of manageable activities that reliably increase personal happiness. Several of them-including the top three on her list-require nothing more than a pre-suasive refocusing of attention:

- Count your blessings and gratitudes at the start of every day, and then give yourself concentrated time with them by writing them down.

- Cultivate optimism by choosing beforehand to look on the bright side of situations, events, and future possibilities.

- Negate the negative by deliberately limiting time spent dwell- ing on problems or on unhealthy comparisons with others."

If/when then plans

p. 139–140

"Fortunately, there is a category of strategic self-statements that can overcome these [distractions from our stated goals, e.g. exercising more] pre-suasively. The statements have various names in scholarly usage, but I'm going to call them if/when-then plans. They are designed to help us achieve a goal by readying us (1) to register certain cues in settings where we can further our goal, and (2) to take an appropriate action spurred by the cues and consistent with the goal. Let's say that we aim to lose weight. An if/when-then plan might be 'If/when, after my business lunches, the server asks if I'd like to have dessert, then I will order mint tea.' Other goals can also be effectively achieved by using these plans. When epilepsy sufferers who were having trouble staying on their medication schedules were asked to formulate an if/when-then plan—for example, 'When it is eight in the morning, and I finish brushing my teeth, then I will take my prescribed pill dose'—adherence rose from 55 percent to 79 percent."

...

"The 'if/when-then' wording is designed to put us on high alert for a particular time or circumstance when a productive action could be performed. We become prepared, first, to notice the favorable time or circumstance and, second, to associate it automatically and directly with desired conduct. Noteworthy is the self-tailored nature of this pre-suasive process. We get to install in ourselves heightened vigilance for certain cues that we have targeted previously, and we get to employ a strong association that we have constructed previously between those cues and a beneficial step toward our goal.

See also: Triggers in the Fogg Behavioral Model

On information overload

p. 147

"Does the idea of having insufficient time to analyze all the points of a communication remind you of how you have to respond to the rapid-fire presentation of many messages these days? Think about it for a second. Better yet, think about it for an unlimited time: Isn't this the way the broad- cast media operate, transmitting a swift stream of information that can't be easily slowed or reversed to give us the chance to process it thoroughly? We're not able to focus on the real quality of the advertiser's case in a radio or television spot. Nor are we able to respond mindfully to a news clip of a speech by a politician. Instead, we're left to a focus on secondary features of the presentations, such as the attractiveness of the advertising spokesperson or the politician's charisma.

"In addition to its time-challenged character, other aspects of modern life undermine our ability (and motivation) to think in a fully reasoned way about even important decisions. The sheer amount of information today can be overwhelming its complexity befuddling, its relentlessness depleting, its range distracting, and its prospects agitating. Couple those culprits with the concentration-disrupting alerts of devices nearly everyone now carries to deliver that input, and careful assessment's role as a ready decision-making corrective becomes sorely diminished. Thus, a communicator who channels attention to a particular concept in order to heighten audience receptivity to a forthcoming message—via the focus-based, automatic, crudely associative mechanisms of pre-suasion—won't have to worry much about the tactic being defeated by deliberation. The cavalry of deep analysis will rarely arrive to reverse the outcome because it will rarely be summoned."

Pre-suasion in action (simple examples)

p. 151

"If we want them to buy a box of expensive chocolates, we can first arrange for them to write down a number that's much larger than the price of the chocolates.

"If we want them to choose a bottle of French wine, we can expose them to French background music before they decide.

"If we want them to agree to try an untested product, we can first inquire whether they consider themselves adventurous.

"If we want to convince them to select a highly popular item, we can begin by showing them a scary movie.

"If we want them to feel warmly toward us, we can hand them a hot drink.

"If we want them to be more helpful to us, we can have them look at photos of individuals standing close together.

"If we want them to be more achievement oriented, we can provide them with an image of a runner winning a race.

"If we want them to make careful assessments, we can show them a picture of Auguste Rodin's The Thinker."

The Real Number One Rule for Salespeople

p. 160

"The Real Number One Rule for Salespeople. I am hesitant to disagree with knowledgeable professionals that the number one rule for salespeople is to get your customer to like you and that similarities and compliments are the best routes to that end. But I've seen research that makes me want to rethink their claims for why these statements are true. The account I heard in traditional sales training sessions always went as follows: similarities and compliments cause people to like you, and once they come to recognize that they like you, they'll want to do business with you.

"Although this kind of pre-suasive process no doubt operates to some degree, I am convinced that a more influential pre-suasive mechanism is at work. Similarities and compliments cause people to feel that you like them, and once they come to recognize that you like them, they'll want to do business with you. That's because people trust that those who like them will try to steer them correctly. So by my lights, the number one rule for salespeople is to show customers that you genuinely like them. There's a wise adage that fits this logic well: people don't care how much you know until they know how much you care."

Social proof information and the problem of uncertain achievability

pp. 163–164 "When I report on this research to utility company officials, they frequently don't trust it because of an entrenched belief that the strongest motivator of human action is economic self-interest. They say something like, 'C'mon, how are we supposed to believe that telling people their neighbors are conserving is three times more effective than telling them they can cut their power bills significantly?' Although there are various possible responses to this legitimate question, there's one that's nearly always proven persuasive for me. It involves the second reason, besides validity, that social-proof information works so well: feasibility. If I inform home owners that by saving energy, they could also save a lot of money, it doesn't mean they would be able to make it happen. After all, I could reduce my next power bill to zero if I turned off all the electricity in my house and curled up on the floor in the dark for a month; but that's not something I'd reasonably do. A great strength of social-proof information is that it destroys the problem of uncertain achievability. If people learn that many others like them are conserving energy, there is little as to its feasibility. It comes to seem realistic and, therefore, implementable."

On authoritative communicators

p. 164–165

"Of the many types of messengers—positive, serious, humorous, emphatic, modest, critical—there is one that deserves special attention because of its deep and broad impact on audiences: the authoritative communicator. When a legitimate expert on a topic speaks, people are usually persuaded. Indeed, sometimes information becomes persuasive only be- cause an authority is its source. This is especially true when the recipient is uncertain of what to do.

...

"A credible authority possess the combination of two highly persuasive qualities: expertise and trustworthiness."

On trustworthiness in communication

p. 165

"Rather than succumbing to the tendency to describe all of the most favorable features of an offer or idea up front and reserving mention of any drawbacks until the end of the presentation (or never), a communicator who references a weakness early on is immediately seen as more honest. The advantage of this sequence is that, with perceived truthfulness already in place, when the major strengths of the case are advanced, the audience is more likely to believe them. After all, they've been conveyed by a trustworthy source, one whose honesty has been established (pre-suasively) by a willingness to point not just to positive aspects but also to negative ones."

On scarcity and loss aversion

p. 168

"Although there are several reasons that scarcity drives desire, our aversion to losing something of value is a key factor. After all, loss is the ultimate form of scarcity, rendering the valued item or opportunity unavailable. At a financial services conference, I heard the CEO of a large brokerage firm make the point about the motivating power of loss by de- scribing a lesson his mentor once taught him: If you wake a multimillionaire client at five in the morning and say, 'If you act now, you will gain twenty thousand dollars,' he'll scream at you and slam down the phone. But if you say, 'If you don't act now, you will lose twenty thousand dollars,' he'll thank you."

Core motives model of social influence from Dr. Gregory Neidert

p. 170

"... any would-be influencer wants to effect change in others but, according to the [core motives model of social influence from Dr. Gregory Neidert], the stage of one's relationship with them affects which influence principles to best employ.

At the first stage, the main goal involves cultivating a positive association, as people are more favorable to a communication if they are favorable to the communicator. Two principles of influence, reciprocity and liking, seem particularly appropriate to the task. Giving first (in a meaningful, unexpected, and customized fashion), highlighting genuine commonalities, and offering true compliments establish mutual rapport that facilitates all future dealings.

At the second stage, reducing uncertainty becomes a priority. A positive relationship with a communicator doesn't ensure persuasive success. Before people are likely to change, they want to see any decision as wise. Under these circumstances, the principles of social proof and authority offer the best match. Pointing to evidence that a choice is well regarded by peers or experts significantly increases confidence in its wisdom. But even with a positive association cultivated and uncertainty reduced, a remaining step needs to be taken.

At this third stage, motivating action is the main objective. That is, a well-liked friend might show me sufficient proof that experts recommend (and almost all my peers believe) that daily exercise is a good thing, but that might not be enough to get me to do it. The friend would do well to include in his appeal the principles of consistency and scarcity by reminding me of what I've said publicly in the past about the importance of my health and the unique enjoyments I would miss if I lost it. That's the message that would most likely get me up in the morning and off to the gym.

On locality and the influence of unity

p. 186.

"Locality. Because humans evolved as a species from small but stable groupings of genetically related individuals, we have also evolved a tendency to favor the people who, outside the home, exist in close proximity to us. There is even a named "ism"—localism—to represent the tendency. Its sometimes enormous influence can be seen from the neighborhood to the community level."

On promoting unity through synchronous responding

p. 196

"It appears, then, that groups can promote unity, liking, and subsequent supportive behavior in a variety of situations by first arranging for synchronous responding. But the tactics we've reviewed so far—simultaneous table tapping, water sipping, and face brushing—don't seem readily implementable, at least not in any large-scale fashion. ... Isn't there some generally applicable mechanism that social entities could deploy to bring about such synchrony to influence members toward group goals? There is. It's music."

Influencing through song

pp. 198–199

"Music's influence is of the System 1 variety. In their sensory and visceral responses, people sing, swing, snake, and sway in rhythmic alignment with it—and, if together, with each other. Rarely do they think analytically while music is prominent in consciousness. Under music's influence, the deliberative, rational route to knowing becomes difficult to access and, hence, largely unavailable. Two commentaries speak to a regrettable upshot. The first, a quote from Voltaire, is contemptuous: 'Anything too stupid to be spoken,' he asserted, 'is sung.' The second, an adage from the advertising profession, is tactical: 'If you can't make your case to an audience with facts, sing it to them.' Thus, communicators whose ideas have little rational firepower don't have to give up the fight; they can undertake a flanking maneuver. Equipping themselves with music and song, they can move their campaign to a battle ground where rationality possesses little force, and where sensations of harmony, synchrony, and unity win."

On the power of pre-suasive openers

pp. 226–117

"The implication for effective pre-suasion is plain: pre-suasive openers can produce dramatic, immediate shifts in people, but to turn those shifts into durable changes, it's necessary to get commitments to them, usually in the form of related behavior. Not all commitments are equal in this respect, however. The most effective commitments reach into the future by incorporating behaviors that affect one's personal identity. They do so by ensuring that the commitment is undertaken in an active, effortful, and voluntary fashion, because each of these elements communicates deep personal preferences. For instance, if through someone's pre-suasive maneuver of showing me images of people standing together I become temporarily inclined toward an inclusive social policy—say, raising the minimum wage for all workers—and I see myself acting on that preference (by making a quickly requested financial contribution to the cause), I will become more committed to the idea on the spot. In addition, if the action was both made freely (it was entirely my choice) and difficult or costly to perform (the size of my donation was substantial), I'm even more likely to view it as indicating what I favor as a person. It's this behaviorally influenced self-perception that would anchor and align my later responding on the issue. And it would be so even if the sequence was instigated pre-suasively by a momentary shift of attention—in this case, to the concept of togetherness."

Modern life and pre-suasion

pp. 228–229 "Modern life is becoming more and more like that bus hurtling down the highway: speedy, turbulent, stimulus saturated, and mobile. As a result, we are all becoming less and less able to think hard and well about what best to do in many situations. Hence, even the most careful-minded of us are increasingly likely to react automatically to the cues for action that exist in those settings. So, given the quickening pace and concentration-disrupting character of today's world, are we all fated to be character of t bozos on this bus? Not if, rather than raging against the invading automaticity, we invite it in but take systematic control of the way it operates on us. We have to become interior designers of our regular living spaces, furnishing them with features that will send us unthinkingly in the directions we most want to go in those spaces. This approach provides another way (besides making immediate, forceful commitments) to arrange for initially formed preferences to guide our future actions. By assuring that we regularly encounter cues that automatically link to and activate those preferences, we can commission the machinery in our behalf."