Daniel Kahneman and What You See Is All There Is

A good story will turn anyone into a sucker. That's the insight of the rule of WYSIATI, a cognitive bias from the 2011 book Thinking, Fast and Slow.

Many years ago in a strange far away land there was a magnificent tiger — one the likes of which the world had never seen before.

The tiger was purple.

Its black stripes ran down and around their luxurious purple fur coat. Sauntering about, fearsome yet garish, the purple tiger ruled over the jungle.

Word got out. People came from all over to see the beautiful beast with their own eyes. They wanted to witness the new king of the jungle.

Do you see him?

Now try to push your purple tiger out your mind. It's time to talk about the reign of stories.

Kahneman's "Machine for Jumping to Conclusions"

Daniel Kahneman, a Nobel laureate for his work in behavioral economics, wrote the 2011 book Thinking, Fast and Slow. The book examined how cognitive biases influence decision-making. Kahneman suggests the mind works by using two modes of thinking — the quick-witted "System 1" and the deliberative, slow-thinking "System 2."

In a chapter titled A Machine for Jumping to Conclusions, Kahneman introduces a core heuristic for the fast-thinking System 1 that he sums up as, “What you see is all there is."

What you see is all there is, or "WYSIATI," is Kahneman's shorthand way of expressing how people become certain — and confident — about what they know, even though what they know is incomplete.

WYSIATI is the tendency to treat a good story, explanation, or idea as all there is to know. Once you know, you can't easily unknow. You struggle to imagine alternative possibilities.

"[You] often fail to allow for the possibility that evidence that should be critical to our judgment is missing —

what [you] see is all there is."

– Daniel Kahneman

Let's look at an example of WYSIATI in action.

How carrots improve what you see at night

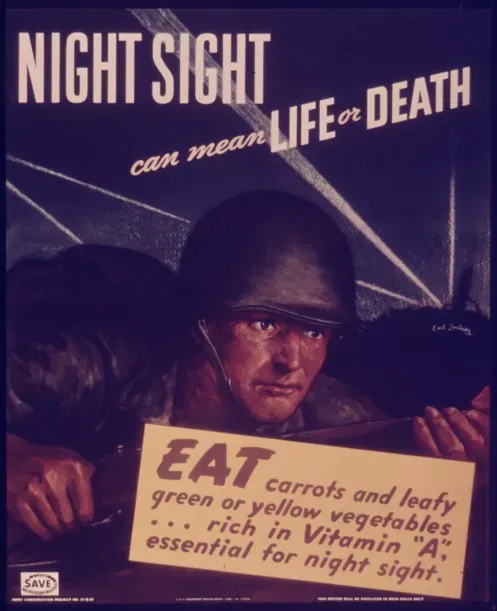

Carrots are commonly believed to be a superfood for improving eyesight. The origin of this belief goes back nearly a hundred years to World War II.

In 1940 German fighter planes were attacking important British targets, and they were attacking at night. Citywide blackouts were adopted to reduce visibility for enemy pilots.

Thanks to a new onboard radar system developed by the Royal Air Force, pilots became able to detect enemy planes in the dark. According to Smithsonian Magazine, "The on-board Airborne Interception Radar ... had the ability to pinpoint enemy bombers before they reached the English Channel."

John "Cat Eyes" Cunningham was one of the first pilots to use the radar system. Using it, he shot down nearly twenty planes at night.

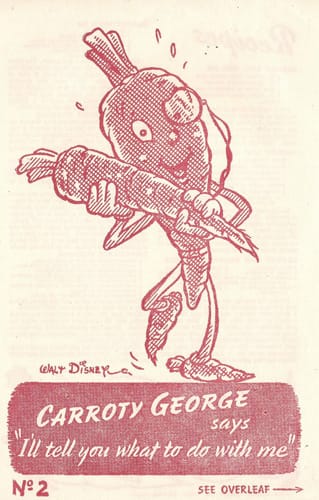

The British did not want the Germans to know of their new, advanced technology, so their Ministry of Information began leaking a story to newspapers: Cunningham, their ace pilot, ate lots of carrots, improving his vision and making it easier to shoot down enemy planes in the dark.

The legend that eating carrots improved eyesight began, and there were many, many additional efforts used to push people to eat more carrots.

Now, whether or not the Germans believed the carroty propaganda is unclear. Regardless, the story stuck. Carrots became the superfood for eyes, and the legend persists to this day.

Why?

Kahneman would tell you that the story fits the facts. Cunningham had an uncanny ability to shoot down planes in the dark because he ate lots of carrots. All it took was a causal nudge to connect the two concepts. The result was a good story that people believed. The truth became irrelevant.¹

This is the power of WYSIATI.

The rule of WYSIATI

The story of carrots illustrates how a good story becomes "all there is." Think of WYSIATI as a way to turn ideas into dictators. A good story establishes a totalitarian state in our minds. Once established, the story can control both what you think and how you think about it too. The rule of WYSIATI is a tyranny of the seen. ... So how do you break free?

Let's return to the purple tiger.

The years went on, and the purple tiger lived his life of prestige and leisure. The purple tiger became a symbol to expect the unexpected because there was no cat like him. None could ever take his place.

Until one day, while lounging on a warm boulder and surveying his kingdom, the tiger was startled to see a new cat appear. Except this was no tiger. No, it was something neither the tiger nor anyone else had never seen before — a beautiful lion, one with a mane like the lead singer of an '80s rock band:

The lion was purple too. Just like that, the true king returned, and everything changed again.

This story about purple tigers and lions illustrates two concepts about WYSIATI.

- The purple tiger exemplifies how you can stand up ideas in the minds of anyone, and with story, the ideas become difficult to displace.

- The purple lion exemplifies the same idea, but used to subvert and displace an existing idea. A purple lion hadn't crossed your mind — not until it was written into existence. Purple lions teach us how to use a new idea to push an old idea out.

The story illustrates how "what you see is all there is" can be used offensively and defensively. WYSIATI works against WYSIATI.²

WYSIATI is stories

You see that WYSIATI works, but why? WYSIATI is stories. Stories are humanity's richest format for knowing. They mix fact and detail with frame of reference and relationship. The result is a complete, dense set of information.

Just remember: Stories aren't really complete. Stories leave out details. Stories connect the dots regardless of whether or not the dots should be connected. Remember back to the carrots and the ace fighter pilot. The story was believable and coherent. It made sense. But it wasn't the truth.

Because the truth didn't matter. Once a story takes hold, that story becomes all there is. Kahneman put it this way:

You cannot help dealing with the limited information you have as if it were all there is to know. You build the best possible story from the information available to you, and if it is a good story, you believe it. Paradoxically, it is easier to construct a coherent story when you know little, when there are fewer pieces to fit into the puzzle. Our comforting conviction that the world makes sense rests on a secure foundation: our almost unlimited ability to ignore our ignorance.

That "unlimited ability to ignore our ignorance" represents a scary opportunity available to every person³, every company, and every brand. The only question is how will you put the power of WYSIATI to work?

Now that you know about WYSIATI, you will see it everywhere. You'll start to notice the stories being pushed on you as well as the stories you've embraced in your day-to-day life. That's because WYSIATI is a recursive, self-reinforcing frame. Similar to how unusual framing makes a phrase stand out in your mind — the Baader-Menhoff phenomenon — WYSIATI is yet another way to express an ancient observation about people.

Here are several related expressions to WYSIATI:

• More than 2,500 years ago, Theognis of Megara wrote, "πολλάκι γὰρ γνώμην ἐξαπατῶσ' ἰδέαι," which translates to "the outer image often misleads your judgment" (H/T Nassim Taleb | Source of translation)

• In 4th century BCE, you had Plato's Allegory of the Cave

• More than a thousand years ago: The blind men and the elephant

• One hundred years ago, René Magritte's 1929 work The Treachery of Images.

• In 1933 was Alfred Korzybski's assertion that the map is not the territory

• In 2007 Nassim Taleb wrote of the "narrative fallacy" in his book The Black Swan.

• Kahneman popularized WYSIATI in 2011.

How to make stories work for you

Move over turtles, it's stories all the way down. Behind every choice, every behavior, and every belief is a story used to make sense of the world.

Here are two ways to put WYSIATI to work:

1. Offer them a better story

Return again to the purple tiger and the purple lion. The story of the purple tiger represents how to stand up a new idea. Though there are no purple tigers, it's fairly easy to imagine what they'd look like. You know what a tiger looks like. You know the color purple. Your imagination makes the magic happen.

If you are working with a novel product or service, your job is to connect your offering to concepts your audience already knows. How you connect them must be different, and the resulting story must be better than the one they already have.

How much better? If what you offer your customers isn't an order of magnitude better than what they have already (See Peter Thiel's 10X rule from Zero to One), you need figure out how to use your story to reframe the way they think. How can you position your offering in a way that's different, impossible to ignore?

Our purple lion shows us that this is possible — you can push out an old idea with a new one. Remember that the rule of WYSIATI is always in play — you may be too close to the subject matter to see it differently. Consider calling in an outsider to help.

2. Reveal a connection they haven't yet seen

FedEx is a global brand identity, and most folks know that hidden in the white space of their logo between the "E" and "x" is an arrow pointing to the right:

Once you see the arrow, you can't unsee it. This design choice makes the FedEx logo different, interesting. The arrow suggests the motion of shipping goods, which reinforces their brand story.

Similarly, the logo for R-ght contains the missing letter "i." You just have to see it: The "i" is turned 90° to the right, suggesting forward motion, which aligns with R-ght's tagline, "How ideas go forward."

You must connect the dots for them until they start connecting the dots for themselves. The best marketing aligns your story with your product or service.

If you don't have a good story for your brand yet, you're in good company. There are many examples of products that launched with one story only to change it later. What's most important is you're clued into how your product or service is being used, observing closely the Job-to-Be-Done. Take care to listen to the stories your customers tell. As you understand those use-cases, you can adapt your stories.

For example, Kleenex was first launched in 1924 and marketed as a cold cream remover, but Kleenex customers found many other uses for the product — like blowing noses. So in 1930 Kleenex changed how they marketed the product to reflect the better story (See When was Kleenex inventend?). Now, Kleenex is synonymous with dealing with sneezing, coughing, nose-blowing, and more — so much so that nearly 100 years later people think of Kleenex as another word for tissue.

Similarly for millions of people smartphone means iPhone, online video means YouTube, or spreadsheet means Excel. This is all WYSIATI in action.

This is the power of story.

What more is there?

WYSIATI is a powerful frame for understanding how stories constrain what and how we think.

Stories offer the power to shape thoughts, to place facts in a context of your own design. A power not to be trifled with, take responsibility for stories you tell yourself — and craft stories that change minds and even teh world.

Never forget there's more to every story — if you're open to seeing it.

This article is part of a growing collection of frames for understanding what's right for people — in order to build better businesses, products, and services.

Footnotes

¹ Yes, beta-carotene or Vitamin A is good for eye health — as are many other essential nutrients. But Vitamin A is not uniquely available through carrots. It's in all sorts of leafy greens and also abundant in eggs. So why carrots? Perhaps because carrots are a vegetable, bright orange (though sometimes purple), and could be branded alongside the Cunningham story.

² Parents know the stickiness of WYSIATI from experience. It's futile to tell a child who's afraid of the bogeyman under their bed that, "It's not real. Just go to sleep!" These protests do nothing to displace the monster. Instead, a mom or dad might try to cast a spell. Do an anti-monster dance while speaking a silly incantation, "Toola-zoola-dee, toola-zoola-doh! Any monsters here? It's time for you to go!" What works for kids works for adults too.

For example, there are many ways to deal with anxiety. But the head-on approach — rationalizing — may not be the best. Instead, the next time you become anxious, become aware that you're worrying and let that awareness be your trigger for practicing a new habit. Remember a fond summer experience from your childhood (or a recent summer vacation). Let your mind take you to that place and time, remembering who was there, what it felt like, what you did.

³ Nowhere is the power of story more important than for individuals. Everyone examines their existence through the filter of their stories. Stories about your career, your family, your relationships, your strengths, your weaknesses — these stories exert incredible influence. Though it's beyond the scope of this article, consider reflecting on the stories you tell yourself. Are they helping you or harming you? How might you tell them differently? What aren't you seeing?

As you remember, follow those experiences wherever they lead. Soon you may have forgotten your anxiety completely. Try it.